IN CONVERSATION WITH is a series from Archetype where we interview artists in/at the edges of crypto across music, visual art, design, curation, and more.

Sofia Garcia is a generative art dealer, curator, and founder of ARTXCODE, an artist management and curatorial platform specializing in generative art. She sits on the board of directors at Code/Art, where she has been championing young girls’ and women's introduction to creative coding since 2015.

Over a call, I chatted with Sofia about digital art display, institutional interest in digital art, the platformization of art collecting, and more.

The following interview has been edited and condensed for length and clarity.

Katie Chiou: For those who may not be familiar with your work, can you share more about your background/journey as an art dealer and curator?

Sofia Garcia: In college, I was studying art history and began working at art galleries. I took a coding class in order to increase my chances of employment because I didn’t feel like I was going to be able to support myself in the traditional art space. My worldview shifted during that first class when I realized code dictated everything around us, and we had the power to shape it. Technology became a very human-focused endeavor to me. Before that, it just felt like this omniscient presence that existed. So I became really fascinated with the history of computer-generated art and made that my full-time job outside of school. There wasn’t much out there on the subject, so a lot of it was self-study.

ARTXCODE started as an anonymous Instagram account where I was trying to find people who cared about creative coding—or more accurately, were creating art with code. People started submitting their artwork to be featured. I was posting tutorials, just trying to find people who cared about what I cared about. It was really special.

After college, I moved to New York and got a job at JP Morgan as a developer. I used that extra income to start collecting artwork. I started collecting, going to art and blockchain events, and that’s how I found out about the Contemporary and Digital Art Fair and partnered with my dear friend Sebastian Sanchez to put on our first exhibition featuring works by Tyler Hobbs and Dmitri Cherniak. It changed everything. We experimented with our first NFTs. All the work sold. Suddenly it was like, “Okay, I guess I sell art now.”

In 2021, I left JP Morgan to organize a large exhibition in Miami for Art Basel. I was frustrated by how the conversation around generative art had been hijacked by the broader NFT craze. Auction houses were showcasing the work in ways I found really frustrating and, honestly, disrespectful to the creative culture. In 2022, I joined forces with my now co-founder Toni, and we decided to start representing artists through ARTXCODE. It was an interesting decision in the age of self-serve platforms and generative art sales, but we wanted to take a more holistic approach to the space: how can we influence the culture by partnering with platforms, not competing, to make sure there’s strategy and intention behind all these releases with our artists?

KC: Was there a specific artwork/artist that inspired you to dive deeper into digital or generative art?

SG: It initially started with a fascination with the history of computer-generated art, not necessarily code-based artwork, but computer-generated art. Even things like the introduction of Photoshop or the first videos made with computers, that was all really fascinating to me. But the more I dove into my own education in code and creative coding, the more that became my focus.

In the beginning, ARTXCODE was meant to be a corner of the internet for new media art. But I quickly realized there could be a lot more strength to the narrative if I was more specific about the type of artwork that was curated there. Around 2018 or 2019, I decided to focus just on creative coding. That was what the space was called at the time. Now we might call it generative art or algorithmic art, but back then it was just creative coding: a bunch of friends who loved to code and make art in their free time, sharing it online. That was the community I aligned with the most.

The Processing Foundation was a big part of that. Big shoutout to Dan Shiffman for what he's done with The Coding Train on YouTube, it was hugely impactful for my education. And of course, Vera Molnár is an absolute legend. Vera and Lillian Schwartz were both incredibly early, pioneering figures of the creative coding space.

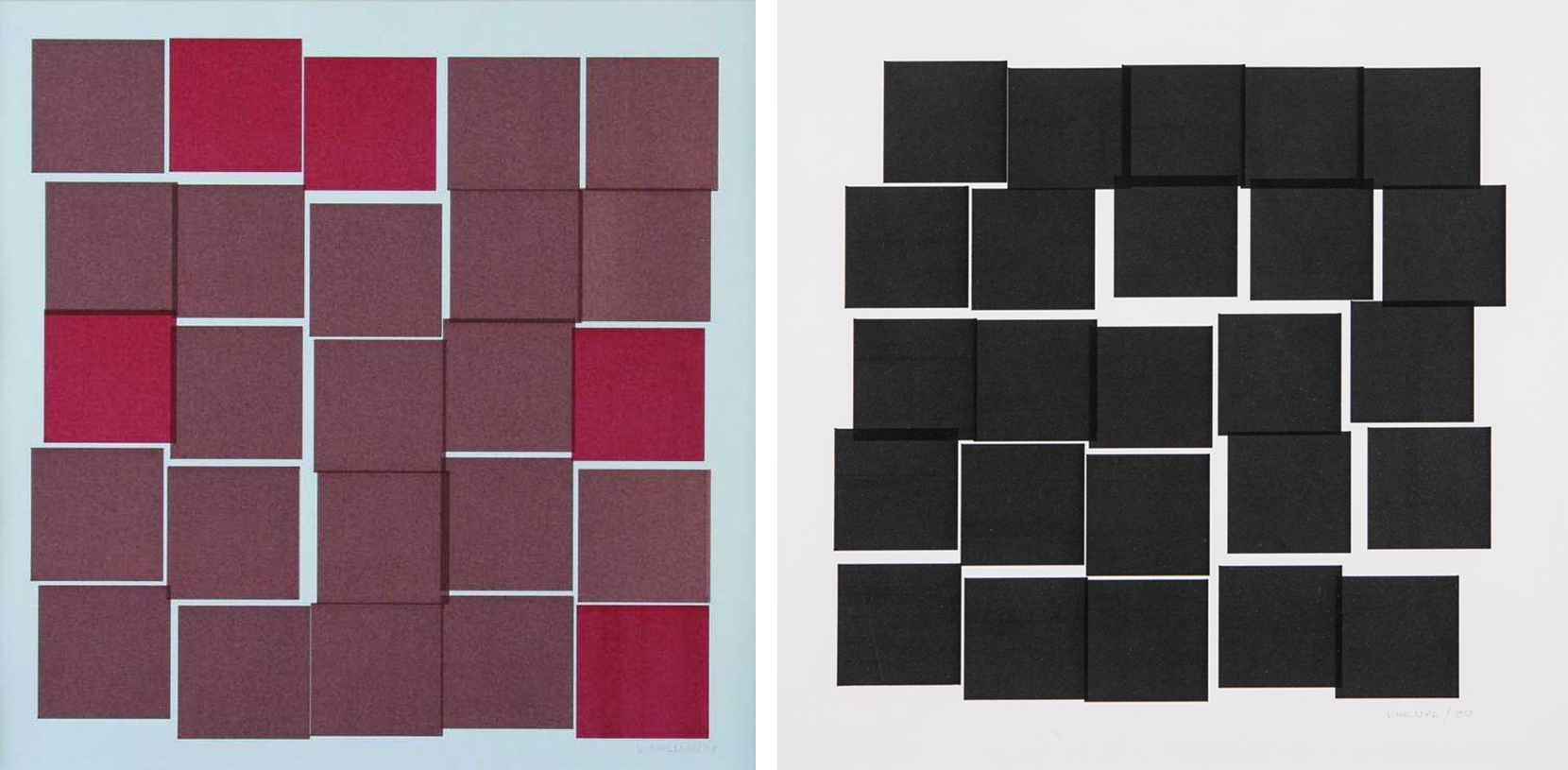

One of the first artworks I tried to recreate with Processing was Molnár’s 25 Squares—a grid of 5x5 squares. You write an algorithm to randomly rotate each square by 1 to -1 degrees, and maybe randomly change some colors. It looks so simple, but it’s an exercise that really drives home what it means to create a system to produce art. 25 Squares was one of those pieces that really nailed that in for me.

KC: Going back to something you said earlier, can you speak more to how you thought traditional auction houses weren’t engaging with generative art well? What specifically were you seeing?

SG: I would say a lot of it came with display, but there was one specific moment that was impactful for me. There was a work I had curated and sold to a collector a year prior, around 2020, and it was a piece I was very attached to. I found it in the artist's archive and thought it was really special. It was a 1:1 ratio, so a square, and the next year it went up for auction and sold for $1.5 million. I had originally sold it for a little over $1,000.

At the auction, the work was exhibited on a TV screen with black bars around it, and that just infuriated me. The piece was so powerful, and display matters. When you throw an artwork up on a TV screen just because it’s digital, it takes away so much of its power. Especially at that price point, seeing a work displayed so haphazardly is really troublesome.

It’s also very difficult to explain the value of digital artwork to someone when it’s treated so haphazardly. Why did that sell for $1.5 million? Why does it look like that? It could’ve been so easy—make a print, find a square screen, anything other than just throwing it up on a TV and calling it a day.

KC: How do you think about the importance of semantics when describing generative art, code art, algorithmic art, etc.?

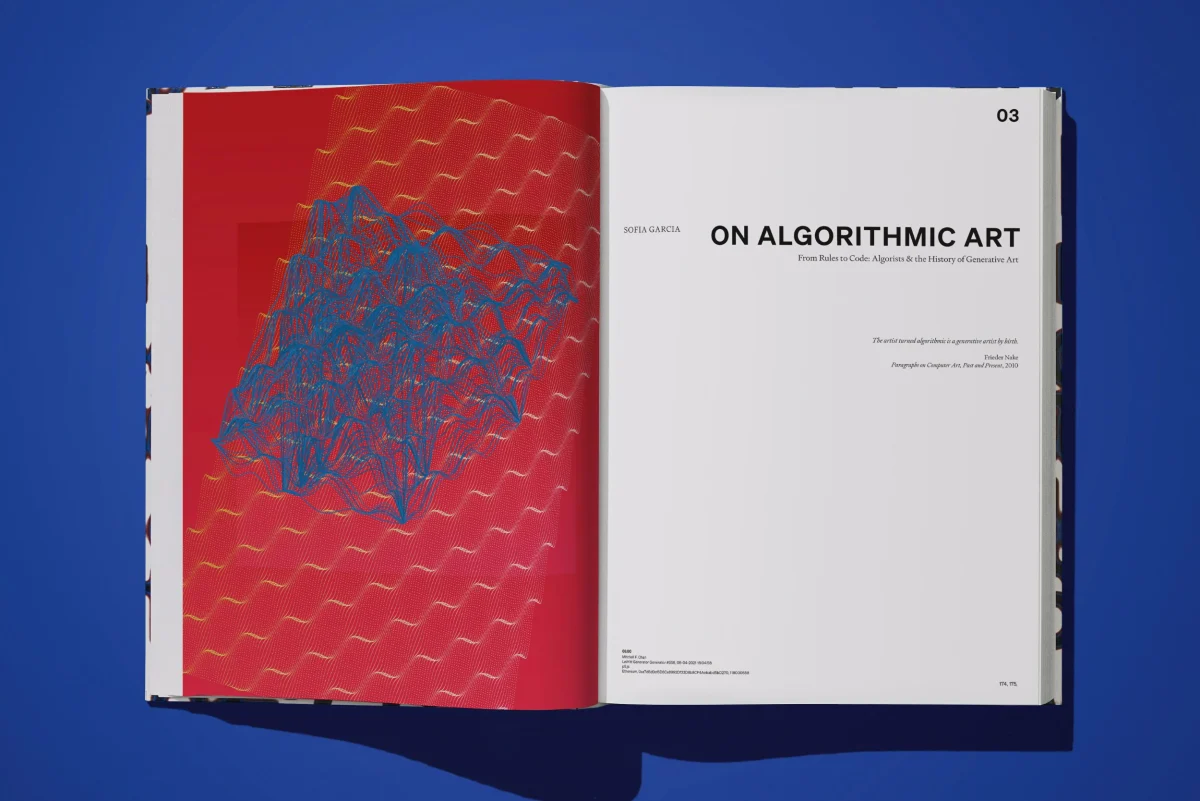

SG: I recently published a chapter in TASCHEN’s book On NFTs where I dive into this discussion around the taxonomy of digital art. There are some great references, Margaret Boden wrote a wonderful paper on the different types of generative art. I think there’s often an assumption that generative art equates to digital art, and that’s not always the case. Generative art is an umbrella term describing anything created with systems, which doesn’t necessarily have to be computational.

In the context of what I focus on, I think “algorithmic art” is a great term—works made with custom algorithms. There’s also AI-generated artwork, generative AI work, and code-based art, which opens up another conversation. For example, net art—works made with HTML and CSS—doesn’t necessarily operate in the same way algorithmic art does.

There are many ongoing discussions about what these terms mean and what they define. We’re still so in it that it’ll take time to really hone in on how to describe these pieces. Even within blockchain contexts, we’re seeing new categories emerge—like protocol art, which is often defined as art about technology made with technology, where smart contracts and the blockchain become the medium.

Everyone’s still trying to wrap their heads around it. How do we define computational or digital art, pre- and post-blockchain? How do we talk about algorithmic art, pre- and post-LLMs? It’s a fascinating and ongoing conversation I always welcome.

KC: Apart from terminology, how do you think the space broadly has evolved since you first became involved?

SG: Early on, it was a tight-knit group of people tinkering and building in their free time, sharing work because they were proud and excited. There was no monetary upside, and no expectation of one. Some of the early works I bought from now-major artists were under $100—they were just excited someone was interested in their work.

Once 2021 hit, the NFT run was overwhelming—for artists, for curators, for everyone in the space who had come in with genuine intentions. Watching the narrative get hijacked was disheartening. We still deal with it: loud commentary on Twitter coming from a wrong or misguided mental model. People talk about this artwork without historical context, framing it mostly in monetary terms.

That’s a big part of what I’m trying to address now, especially with the course I’ll be teaching at NYU—providing historical context to help people better understand how this space has evolved. One of the reasons I started representing artists was because of how intense and overwhelming the space became. Everyone was launching a generative art platform. Artists were inundated with “opportunities.” That’s always been the hardest part—finding the balance. But I think things have calmed down now. The dust has settled. The people still here are genuine. That’s not to say they don’t have investment theses. People collect for many reasons. But there’s more fundamental appreciation now.

The conversation around and expectations of financial gain was one of the hardest things for a lot of us to grapple with. That’s why I take so much pride in the work we do at ARTXCODE—as dealers and stewards of what our artists are doing, and the community at large.

KC: I imagine it’s a double-edged sword for the excitement and energy in the space to settle down, what has your experience of that been like?

SG: The crazy momentum of the space around 2021 definitely tripped me out. Of course, I was genuinely happy to see my friends make life-changing money. But I also had this sense of impending doom, it didn’t feel sustainable. Going from selling a few works for a couple thousand dollars to suddenly seeing one of those pieces go for millions just isn’t a long-term model.

I was worried about what that would mean for artists and their long-term careers, especially around price discovery. As someone who cares deeply about all this, I went from being able to buy work for a few hundred dollars and support artists directly to being priced out. Finding collectors with that level of wealth is rare, especially for artists who haven’t even been making work for ten years. That’s hard to reconcile.

We’ve seen artists really struggle after hitting an all-time high—because where do you go from there? If you want a sustainable career, there has to be some price correction. That’s something we take seriously now with our artists. We try to be conservative and strategic about pricing. We’re not trying to create wild swings. It doesn’t help the artist, and it doesn’t help collectors. Sustainable growth is what matters. I want the artists we work with to have careers that span decades.

KC: What has your experience been like on the institutional side and working with those sorts of stakeholders?

SG: There are always interesting conversations happening on the institutional side. I’ll give the auction houses some credit, even after some of the criticism I’ve shared.

At this point, I’ve worked with several of them. With Sotheby’s, for example, I helped curate one of their Natively Digital auctions. Not only that, I went out of my way to produce the show. I was on-site, making sure everything was installed properly. I said, “I don’t want to see a single wire.” I talked to them about how to display the artwork in a way that would serve both the show and the artists.

Later, when we worked with Sotheby’s on their first onchain generative art release with Vera Molnár—who I mentioned earlier, and who was 99 at the time—we had to have some hard conversations. The team had certain sales-driven ideas about what they thought would make the work sell, based on current trends. I had to push back and explain how and why those ideas didn’t align with the artist’s practice. I understand the sales goals, but we have to respect the history and do it respectfully.

That’s one side of the work: making sure these initiatives are executed with intention, not just maximum extraction. The other side is providing as much context as I can—helping institutions understand the space and ensuring it’s approached respectfully. Sometimes that means working with museums, answering their questions, explaining why they should pay attention to this work, or just supporting them however I can.

KC: What do you think institutional interest in the space looks like now?

SG: In the last two years, we've really seen a giant influx of institutions come in and start acquiring this work, whereas beforehand they would have never touched it with a ten-foot pole. So I think while this dust has settled, we’ve got some really key, important institutions coming in and acquiring work pretty low-key. And I think that's the most exciting part. There are already institutions that have beautiful collections. People don’t think about the Victoria and Albert Museum in London as being a haven for early digital artwork, but their collection is out of this world. It's one of the most amazing early computer art collections I’ve ever seen, thanks to a donation by Patric Prince.

Honestly, I’ve got to give props to Europe. A lot of the European institutions have really stepped up across places like the Pompidou and the Jeu de Paume in Paris, the National Gallery of Finland, and the National Gallery of Denmark to name a few. I’m really impressed with what the institutions are doing in Europe and their openness to digital culture.

In the US, you typically see approaches where museums will say that they’ll consider acquiring an artwork for the museum only if the artist does a sale with the museum first.

KC: How do you think about the role of platforms in display and discovery for digital art, as opposed to artists launching/releasing their own work?

SG: I think there are instances where it does make sense for an artist to own their release. I think there’s a time and place for that, and it can be really appropriate. But there are also really lovely galleries and platforms that have proven track records of doing great work. We love working with Fellowship. We’ve really enjoyed working with Verse. Heft Gallery just opened here in New York, and we love working with Heft. There are some really great partners out there, and when we all come together, it's like magic. There are also instances where we’ll do our own releases as ARTXCODE. But from a really early point, I knew I didn’t want to be a platform in competition with other platforms.

So, there are plenty of platforms we adore and love working with. And there are others where we tried it, didn’t care for it, and moved on. It’s our job to work with the artists to figure out what makes the most sense for their work.

KC: Do you imagine a world in which artists start launching their pieces and collections on their own platforms or websites?

I think that makes a lot of sense. And there are artists who’ve done it successfully. Maybe they’ll partner with an organization like Transient Labs. There are artists we've worked with who will create their own online ecosystem for minting, and we’ll come in as partners to help support the narrative, introduce it to collectors, things like that.

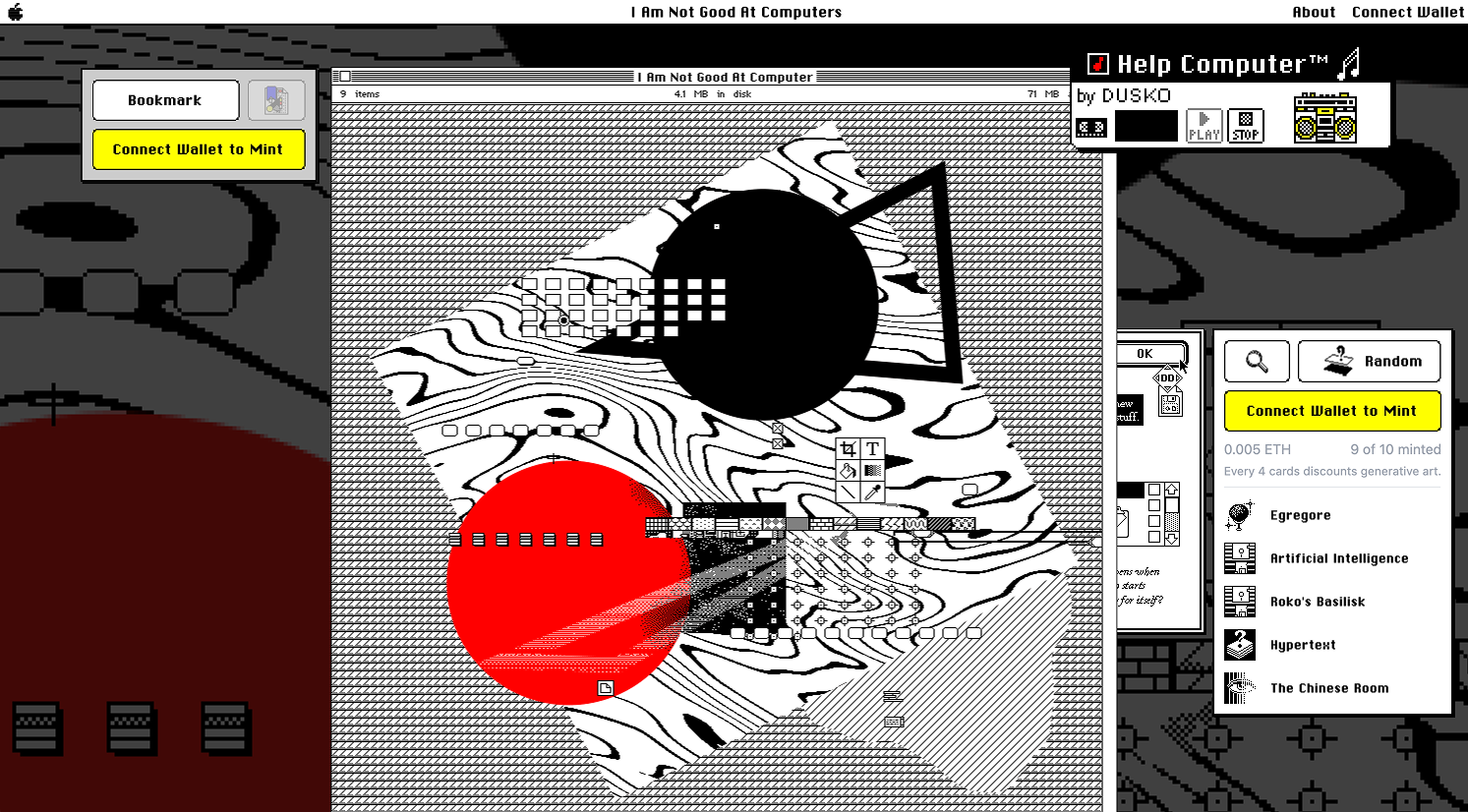

Even projects like I Am Not Good at Computer by Sgt Slaughtermelon, it wasn’t just your typical mint site. It was a world he built that you could go into, listen to music, explore the hypercards. It’s a really lovely example of this new wave of net art or internet art engaging with the blockchain. It’s fascinating.

There are upcoming releases that we think really should be standalone websites rather than being put on a platform. There’s just a stronger narrative there. It feels more artist-owned, artist-designed. You enter a world, rather than just landing on a static, somewhat modular and systemic approach to collecting art.

Even when we think about secondary markets, this plays a role. When we look at early Art Blocks projects—or Art Blocks projects in general—it was always fascinating to me that the more still, illustrative work performed 10,000 times better than the really engaging, interactive, or animated works. That’s largely because of the way secondary marketplaces function. Their layouts are grid-based, and you typically see a still image. To actually experience the work, you have to click into it and see how it behaves or interacts, and that’s not always conducive to the best viewing experience. I think it's amazing when artists create their own worlds. It gives you the space to really step into what they're creating in the first place.

KC: How do you think management/representation of a digital artist is different from how representation might work for a more traditional artist?

SG: Education is a huge part of it. I think there are always many misconceptions around what it means to collect and experience digital art. It's not only about educating collectors on how to engage with the various different types of digital art that exists, but also acknowledging that there are trends where collectors actually might not want to collect a work if there's a physical component.

This is something that we've come across, which is very different from the traditional art world, where there's an assumption that in order for art to be real, it needs to be tangible. Whereas in our experience, there have been times where I've had multiple collectors say no to an artwork because there was a physical counterpoint.

So I think that the relationship between the digital and the physical is a huge conversation where there's no one-size-fits-all approach to it, but it's really fascinating. I try to push artists to consider new mental models of how to potentially think about the life cycle of a digital artwork.

For example, it's great that you've created a work that is digitally native, but if it was to be exhibited, how would you like it to be exhibited? I'll always chat with the artist and collaborate on different ways to get around this issue. Sometimes, they already have an idea around it, and sometimes I will suggest my own.

I refer to this as the display dilemma around digital art, which I think is a really fascinating one. I also push people to always question the assumption that just because the work is digital, it won't have a physical counterpart. There are plenty of works that we sell that are sculptures, that are plotter prints, or any other sort of physical manifestation—that is also valid.

KC: What proportion of artists or collectors do you work with aren’t interested in blockchain components at all?

SG: In the earliest days, blockchain was never a part of the conversation. It only became relevant to code-based artwork later, and once it did, we saw a lot of artists jump in. Now that some time has passed, there’s a newer school of artists who just don’t want to engage with blockchain. And that’s completely fine.

But I think the most interesting part has been the collectors. Over the last, let’s say, two years, we’ve been focusing a lot on blockchain-enabled or blockchain-backed artworks because of the collector activity we were seeing. A new wave of collectors came in and said, “I really love this work, I understand it’s digital, but I don’t want to deal with the blockchain. Can I just buy it?”

So, instead of minting the artwork, we’ll send them the files, and we’ll create institutional-style packages: how to maintain the artwork, how to take care of it, things like that. It might seem a little backwards, but these are people who often come from a background of collecting video art or new media, pre-blockchain. They’re totally comfortable with this kind of approach.

Another case study was Christie's recent AI auction. We had two works in that sale from artists we represent. Both were physical works—one was a light sculpture, the other was a print on canvas. For that auction, we decided to make minting optional. It was up to the collector. If they wanted what we’d call a digital certificate of authenticity, they could do it. Both works sold for around $10,000, and both went to traditional art collectors. Neither one asked about or followed up on any need for an NFT. So we’re not here to say it has to be crypto. We’re not trying to ascribe that to anyone. If anything, we’re experimenting with it even more now.

A big part of what I’m trying to work on is reaching across the aisle to new media artists who don’t want to work onchain, and who may be making physical works or works that exist in totally different contexts. I want to pair them with collectors who also don’t care about blockchain.

More than anything, my role isn’t to hype up NFTs, it’s to hype up generative art—that came first, and that will always come first. Trying to find the balance in the relationship between generative art and crypto is a top priority for me right now. Being open to experimentation, not rigid in our approach, is a big part of that.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur.

Block quote

Ordered list

Unordered list

Bold text

Emphasis

Superscript

Subscript

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur.

Block quote

Ordered list

Unordered list

Bold text

Emphasis

Superscript

Subscript