IN CONVERSATION WITH is a series from Archetype where we interview artists in/at the edges of crypto across music, visual art, design, curation, and more.

Casey Reas is an artist, educator, and programmer whose work is rooted in software, generative systems, and conceptual minimalism. In 2001, with Ben Fry, Reas co-founded Processing, an open-source programming language and environment for visual arts. He also co-founded the Processing Foundation in 2012 and, more recently in 2020, Feral File, a platform for showcasing digital art. Reas is a Professor in Design Media Arts at UCLA, where he co-directs the Social Software group. His art, ranging from prints and paper works to large-scale installations, has been exhibited internationally and is held in major public collections (e.g. Centre Pompidou, LACMA, Victoria & Albert Museum, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, etc.).

The following interview has been edited and condensed for length and clarity.

Katie Chiou: For those who may not be familiar with your work, can you share more about your background/journey as an artist?

Casey Reas: I'm an artist and educator. I've been teaching at UCLA in the Department of Design Media Arts since 2003. I'm an artist who works with code. I prefer the general term artist, but media artist or generative artist are other more narrow ways of zooming in on that. I've always been making work that is code running live as software, and also complementary work from the code that works on paper—printed work as well. I co-founded Processing in 2001 with Ben Fry. Processing is a programming language and environment made to bridge the space in between art and engineering. I'm also a co-founder of Feral File, which is an online gallery that I started with Sean Moss-Pultz and Bitmark in 2020.

KC: In terms of the origin of your interests software and art—code as a medium—where did that come from?

CR: Drawing was always my favorite thing to do when I was a kid, more so than anything else—sports, music—it was always art. When I studied at the University of Cincinnati, I studied graphic design. I was interested in mass media, applied art. I graduated at the time that the World Wide Web was born, and so things moved away from books and magazines into digital space.

When I started working in digital space, I began to slowly understand the potential of software as its own medium. Software typically had been used as a digital version of an analog too. For example, Photoshop was like a darkroom, and Illustrator was like a drafting board. I began to learn how limited that framing was: “What can we do when we start working with software as a medium more directly?”

In order to make the work that I wanted to make, I needed to learn how to code. So I started taking classes at NYU evening school when I was working in New York, and that led me to studying with John Maeda at the MIT Media Lab. At the Media Lab, I was working in a group called the Aesthetics + Computation group. That group’s whole idea was to merge design, art, and architecture with computer science. The work that I've been doing now for the last 25 years all came out of that time that I spent at MIT.

KC: As an educator, how have you observed people’s interest in creative coding evolve over time?

CR: In the past, creative coding was a space that was global, but not very wide-reaching. There’d be a cluster in Tokyo, a cluster in London, a cluster in New York and Los Angeles and San Francisco, etc. During the first era of the World Wide Web, when I first started getting involved in this kind of work, that was an extraordinary moment. It’s the only precedent I can think of for what happened more recently in the past four years with blockchains and creative coding.

When the web happened, all of a sudden, people could share work with each other directly. You could put work on your site, people around the world could see it, people around the world could get in touch with you, and information could flow easily. At that time, almost everybody had their own website, and you would post all of your experiments and studies and the kinds of visual things with creative coding that you wanted other people to see. A community developed around that.

And then in the early 2000s, after the dotcom boom and bust, there was even more energy around the web space, and some institutions started to get interested. Things like Rhizome originated around 1995 and were starting to support people in New York doing web-based work. Different museums and curators, like the Whitney Museum of American Art, were commissioning work and putting it online.

Artist interest gave way to some institutional interest, and then I think energy fell away over time. Around 2021, everything that happened around creative coding—through hic et nunc and Art Blocks and fxhash—created a huge surge in interest and activity. It was a really exciting moment.

%2C%20Process%3ADrawing%2C%20NYC%2C%20MARCH%202005.png)

KC: What have been some of the big shifts over time in how you’ve noticed different cohorts of your students engage with technology?

CR: When Ben and I created the Processing programming language in 2001, it was very rare to have coding classes in design, art, and architecture programs.

At that time, students were wondering, “Why are we doing this? Why are we learning this?” When you use graphical software—things like Adobe—you're only at the very surface of how the computer can be used as a medium. But when you can make your own tools, when you can imagine your own systems and be able to get closer to the true potential of what that medium can do, that's when you start to explore even more. You can become even more of an author of what you're making, rather than doing the kinds of activities you can do with a computer that are built into software that somebody else wrote for you.

That was the first stage—constantly getting asked why. And then terms like “creative coding” began to be used. It became something that was acknowledged and understood that this was something practical and useful that we're learning, even if we're not going to be programmers. As designers, as artists, it helps us understand what software can do. It helps us work and collaborate with other people.

That's been the basic journey. But still, at that point, people who are hiring people to be creative coders, it's not a very large community. It's always been more of a niche. But in truth, some people are strongly motivated at both visual art and coding. Some people are really talented at both. And those people, people like myself, you're not satisfied just doing one or the other. You want to integrate these things together.

KC: I’ve spoken with some artists who feel that the digital tools one uses can often “date” their work, i.e. the original Midjourney aesthetic. Curious if you have thoughts around that and how you think about the roles of your tools in your practice?

CR: When you’re writing your own code, making your own software, building your own tools, you can have more of your individual vision and your personality in the work. You’re not using other people’s vision of what computers are for. Typically, over time, whatever new feature Photoshop has, or Procreate has, or whatever tool has, really constrains how you can express yourself. And as those tools change, as they gain new features, the kinds of expressions people can make change.

I think that’s where things begin to beg the question: “Who’s really the author here?” “Is it the people who are making the tool, or is it the person using the tool?” I think any artist can develop a kind of control and fluid use of a tool and surpass what it can do. But I think for people who are first learning, or people who don’t go that deeply, the tool has a really strong presence and voice in the work that people make.

KC: What was your foray and interest into blockchains and NFTs like?

CR: With physical things that are the more traditional media for art, you can keep track of things because there are physical objects that you hand from one person to another. With digital things—the kind of work that I’ve been making—I’ve believed in blockchain for a really long time as a way of keeping track of work. What work is in whose collection, what work was actually created, what work is registered?

Having those traits and processes completely open is something that goes hand-in-hand with a lot of the open-source work that I’ve done for a long time. It makes a lot of sense to me. I did a lot of collaboration with a blockchain company called Bitmark whose idea was to use blockchain for property rights.

We did a lot of experiments together, and that’s what led to Feral File, which is an online gallery that I co-founded along with Bitmark, and specifically in tandem with Sean Moss-Pultz, who was the CEO. The idea of Feral File was to make opportunities, to make a place where artists can release work, register it, and make that work available to collectors.

Beyond the logistics, Feral File was also about reimagining how curation and community operate online. It’s a platform where artists, curators, and collectors can collaborate through shared systems, bridging the openness of software culture with the intentionality of exhibition-making.

A huge shift happened in 2021. People had been making art with software for a very long time—for over 60 years, but it was a small community. In 2021 that energy completely expanded, and now there are thousands of people who are collecting this kind of work.

And I think that a lot of things had to happen to lead to that. One was having blockchains where you could openly register work. Another was having really fast computers in your pocket. And then another was having cryptocurrency, which allowed it to be easy to sell and collect work digitally.

KC: When founding Feral File, was there a specific feature or component or positioning that you were really interested in, in terms of differentiating from other platforms that were popping up at the time? Or was it more the sense of “more is always better,” for the diversity of audiences, tools, and formats?

CR: The only time I ever create something is because I need it, I want it, and nobody’s made it before. In 2001 with Processing, there was nothing like it at the time. There were no programming languages made for artists and designers and created by artists and designers that occupied the space in between engineering and art. Same with Feral File. Nobody, at the time, was supporting software-based work, generative art, the kind of stuff that I care the most about.

The other thing that Feral File did differently was that we launched with group shows. I strongly believe in the power of starting with a curator. The curator picks the artists and then works with those artists in a community to build a show together. Feral File started with that from the very beginning. The other thing that was unique about those early Feral File group shows is that all the works were sold in the same edition number and all for the same price to collect as well. There was a strong sense of equity in the way we presented that work.

KC: On the collector side, do you feel like you have, or have ever had, a sense of who your collectors or broader audience are? Do you feel that matters to you, emotionally or logistically? How do you think about engaging with the folks who are engaging with your work?

CR: I think like most artists, one of the major reasons that I worked with galleries for so many years was because I didn’t want to engage with collectors. I didn’t want to talk about money, I didn’t want to talk about sales of the work. I wanted somebody who was a specialist in that area to do that. I wanted to focus on the work. That was one of the many things that’s been surprising about minting work, it’s no longer desired to have that arm’s-length distance. It’s become interesting and positive to have more direct dialogue and engagement with collectors.

When you’re making physical work and putting it in galleries, oftentimes I would work for a year to make 12 or 15 things, have it in a gallery for a month, and then the show would go down. That work would often sell over the course of the next decade.

Then, over 2021 and 2022, I released many thousands of artworks—mostly long-form generative—that were all collected within the first two minutes that the work was released. It was such a different model. The accessibility, the immediacy—like going back to the 90s, people being able to get in touch with each other, being on Discord all the time and in DMs all the time—I learned that it can actually be really engaging and positive to have relationships with different collectors.

KC: When you founded Processing, I imagine it was very different in terms of how you were getting in touch with people, like going on an education circuit, building that community. Was it very different, vaguely similar? What was that experience like?

CR: It was completely different. The creative coding community was much smaller, but very active in the early 2000s. There were no financial transactions, nothing was monetized. People would make things, share them, hang out in forums, and talk about each other’s work. There wasn’t even an idea that the work could be bought, sold, or collected. All the software we were using, like Processing, from the very beginning was completely open source. It was made by the community. There was no funding for it.

In 2012, we created the Processing Foundation (eleven years after founding Processing) as a way of funding software development. The community had gotten so big, the software so complicated, that we needed a mechanism for working with money. But for the first decade, there really wasn’t any. In the early days of Processing, it was a very different feeling: people helping each other because they were excited about making things. Motivations were totally different. Since things began to be minted, there’s still a lot of generosity and community, for sure, but that was the major difference.

Also, in the early days of Processing, the web was completely essential. Sharing work online was completely essential. But I spent years traveling, teaching workshops at different schools. When everything happened around 2021, things were locked down, and everything was happening completely online.

KC: When you started Processing, was there any pressure or inkling of wanting to monetize Processing? Either for your own sake, since you were spending so much time and effort, or even just to sustain the work?

CR: In the early Processing days, neither Ben nor I wanted to do it full-time. We didn’t want that to be our lives. Developing the software was not what we desired to do all the time. I was an artist and educator, Processing was useful for both of those. In Ben’s case, he had a few different jobs in the early days, but he started it when he was a PhD student. He needed a tool for doing data visualization, as he was doing genome visualization work.

While you’re doing a PhD and working as an active artist and teacher, running a software project full time is not the desire. It started as a very small project, meant to be a side project, and there were many years of difficult, often painful growing pains as everything began to scale. At one point, we didn’t want to monetize it, but we did want to be able to hire people to work full time on it. At that time, it was elusive, we weren’t able to raise the funding in the community to do that.

KC: So did it end up mostly being grants and donations that sustained the foundation?

CR: We had a working board—the people who were making the software were also serving on the board. Dan Shiffman was a co-founder, and Lauren Lee McCarthy started really soon after. Lauren is the co-founder of p5.js, which is the sibling project of Processing.

It was through NFTs in 2021 that we were able to successfully fundraise for the very first time. The way projects worked in the early Art Blocks days was that they would highly encourage artists to donate 10% or more of what was made from releasing the work to a nonprofit. A number of artists were using Processing and p5.js in their work, and they wanted to donate to us. That gave us the ability to have enough money to fundamentally change the Processing Foundation—the way it works and what it could support. Now, at this point, I don’t know the exact figure, but maybe there are around six people who are full-time employees of the Processing Foundation. It really changed a lot.

KC: If Processing was founded in 2001 and then Art Blocks was founded closer to 2019 or 2020…that’s almost a 20-year gap before people began donating through Art Blocks. Up until that point, it was just donations from folks, but never on a scale that could support development?

CR: Yeah, never for development. We tried to figure out fundraising for development but were never able to get donations on the scale that would allow that to happen. We were able to get some grants for doing fellowships, we participated in Google Summer of Code year after year after year. But really, Ben Fry, the primary software engineer for Processing, carried the releases almost entirely on his back. I’d say at great personal cost, just making it happen.

KC: Switching gears a bit, you often train your own models and use your own datasets when working with GANs and creating your own work. On a more mechanical level, I’d be curious what your process and stack are, and how that’s changed over time, your experience engaging with these tools at the model and dataset level.

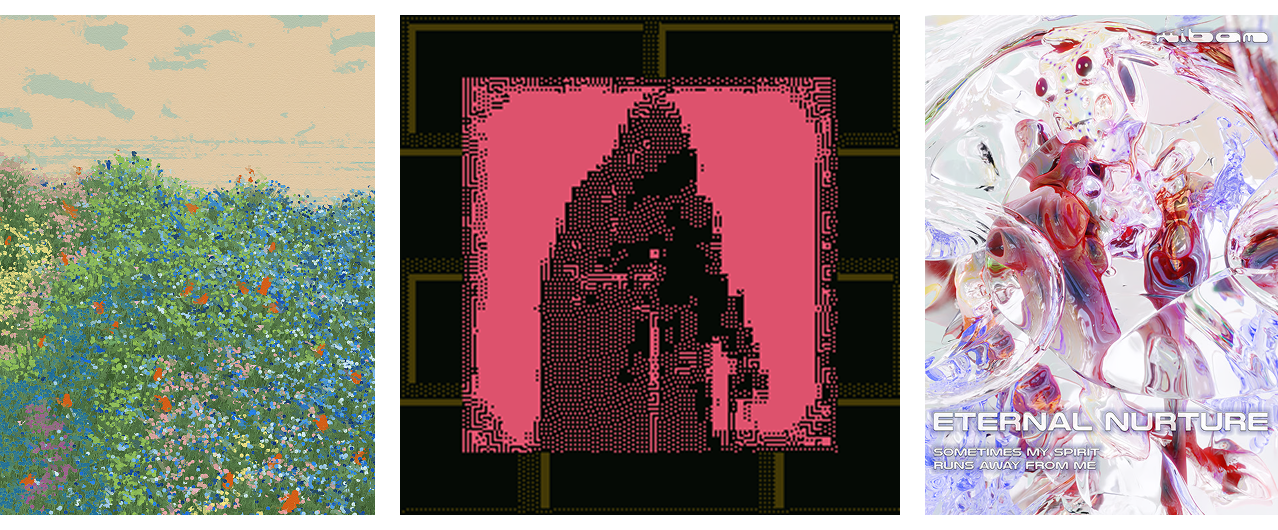

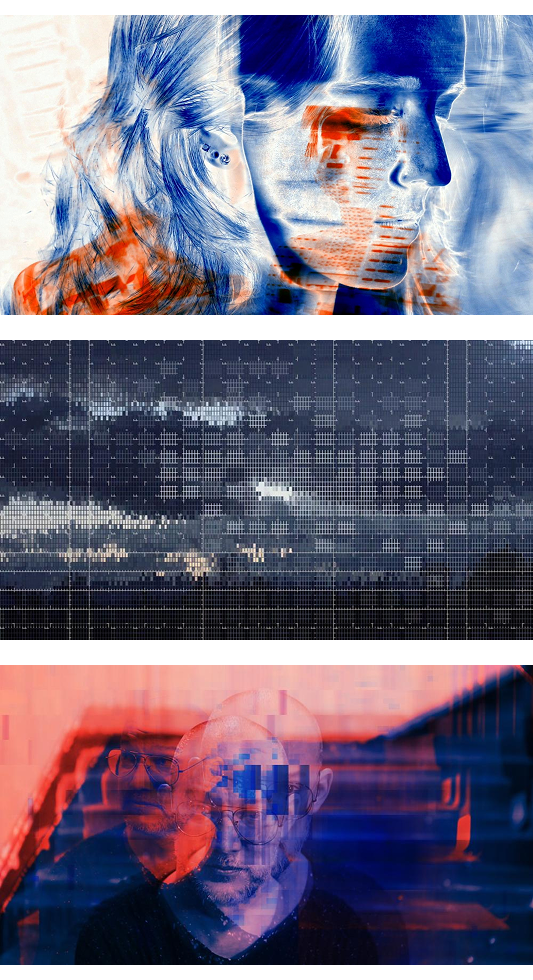

CR: Yeah, so after working with code exclusively for about 20 years, I started working with GANs in 2018, and that was a really big shift because it’s a very different mental model.

For me, it opened up a lot of new ways of expressing ideas. I had always made work that was more related to drawing or painting, and now I was able to make work that was more related to cinema and experimental video, something I’d wanted to do for a long time. In 2017, I made six music videos for a band called The National, and that opened up video to me as a medium. I found my own way through video. To be clear, all those videos were created through writing custom code to process videos so it was related closely to my creative coding practice.

I’m much less interested in large image generation models, but I remain extremely interested in GANs for two reasons. One is the ability to train them from scratch, and the other is the way you can move through the latent space and pinpoint images really precisely. I like being the author of that full process—choosing the dataset precisely, training it the way I want, and then pulling the images and sequences of images from that dataset. It allows a kind of control that I need in the work, a kind of control that I developed, or the desire for which I developed, from working with code for so many years.

KC: Are there tools or platforms you’ve found particularly helpful throughout that process?

CR: Yeah, I’ve been through a lot, as that technology developed quickly. I started with DCGAN, then used Progressive Growing of GANs, and for the last three to four years, I’ve been using StyleGAN. I’ve kind of settled on StyleGAN2 as the main tool that I’m using right now.

KC: You wrote about art collecting in a Medium post in 2019, in which you asked a lot of really interesting questions that still come to mind for me—around balancing scarcity and accessibility, why people collect, and whether those values matter differently across mediums. I’m curious how your questions have evolved in the past six years since that was written.

CR: I wrote that before everything that happened in 2020 and 2021 with NFTs and generative art and before the four years I’ve spent since co-founding Feral File. If I were to write that text now from scratch, it would be so different. One thing I underestimated at the time was how much people simply like to collect things. It’s a natural impulse, but collecting baseball cards is very different from collecting art.

The biggest question in that piece, and still a big question for me, is how we engage with digital media. People engage with digital music all the time. In the past, you needed a physical vinyl record to pass to someone to share something. What digital music has allowed us to do is engage with hundreds or thousands more artists, it’s enriched our ability to explore music. The same is true of digital video. I grew up with three TV channels, that was all the storytelling we had access to. Now we have back catalogs of thousands and thousands of films.

So can the same happen with digital art? Does digital art need to follow the traditional fine art market model, where scarcity defines value, or can it diverge entirely? In the same way you and I might have fifty favorite musicians we listen to constantly, can we have fifty or one hundred favorite digital artists whose work we live with all the time? Can it move from a rarefied, intimidating experience, where people feel alienated from museums and galleries, into something familiar and accessible, like listening to music or streaming movies?

That’s the question. And more importantly, can this transformation be positive for artists? Can artists support themselves and make the work they want to make? Back in 2005, artists working with code could only do it after hours, at night. The promise of NFTs was that digital artists could finally put their best energy into their art. The question now is whether that promise can be sustained for this generation of artists.

KC: What’s on your mind for your own practice these days? Any themes or questions you’re thinking about?

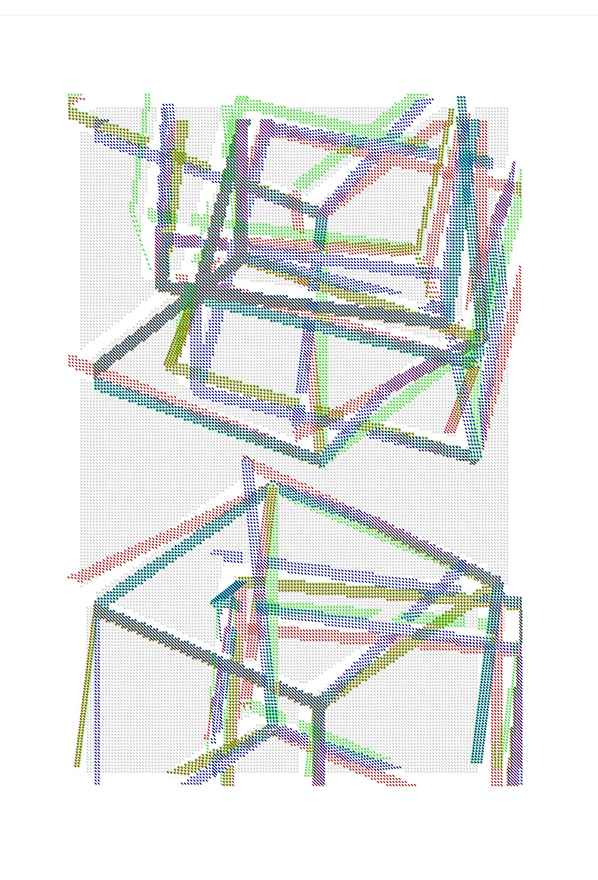

CR: Most of my energy this year has gone into making drawings, nontraditional drawings. They’re plotter drawings: technical, mechanical drawings made with physical ink on paper. They’re based on a series called Atomism, particularly the Still Life works, which are about the history of simulating form in computer graphics—producing these images, then breaking them down into their pixel values, taking the data out of the image, and using it to reconstruct another image. It’s about asking: “What is truly the fundamental nature of a digital image? What lies beyond the illusion? What is the actual nature and structure of that digital image?” The drawings become diagrams of that exploration. I had a show at DAM Projects called Purely Platonic in Berlin in July, that’s my most recent work.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur.

Block quote

Ordered list

Unordered list

Bold text

Emphasis

Superscript

Subscript

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur.

Block quote

Ordered list

Unordered list

Bold text

Emphasis

Superscript

Subscript